When Americans think about corporate lobbyists, they usually think about the people in fancy suits who line the halls of Congress armed with donations, talking points, and whatever else they need to win favorable treatment for their big corporate clients.

They’re right. In fact, corporate interests spend more on lobbying than we spend to fund both houses of Congress - spending more than $2.8 billion on lobbying last year alone. That’s why I have a plan to strengthen congressional independence from lobbyists and give Congress the resources it needs to defend against these influence campaigns.

But corporate lobbyists don’t just swarm Congress. They also target our federal departments like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. These agencies exist to oversee giant corporations and implement the laws coming out of Congress – but lobbyists often do their best to grind public interest work at these agencies to a halt.

When the Department of Labor tried to protect workers from predatory financial advisors who got rich by siphoning off large and unnecessary fees from workers’ life savings, Wall Street lobbyists descended on Washington to try to kill the effort – twice. When they failed the second time, they sued to stop it in the courts.

When the Environmental Protection Agency decided to act on greenhouse gas emissions by passing regulations on methane, fossil fuel companies called in their lobbyists. The rule was dramatically weakened – and then Trump's EPA went even further than some in the industry wanted by proposing to scrap the rule altogether.

When the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau tried to crack down on payday lenders exploiting vulnerable communities, lobbyists convinced the Trump administration to cripple the rule – while the payday lenders who hired them spent about $1 million at a Trump resort.

Regulatory agencies are only empowered to implement public interest rules under authority granted by legislation already passed by Congress. So how is it that lobbyists are able to kill, weaken, or delay so many important efforts to implement the law?

Often they accomplish this goal by launching an all out assault on the process of writing new rules – informally meeting with federal agencies to push for favorable treatment, burying those agencies in detailed industry comments during the notice-and-comment rulemaking process, and pressuring members of Congress to join their efforts to lobby against the rule. If the rule moves forward anyway, they’ll argue to an obscure federal agency tasked with weighing the costs and benefits of agency rules that the rules are too costly, and if the regulation somehow survives this onslaught, they’ll hire fancy lawyers to challenge it in court

I have released the most sweeping set of anti-corruption reforms since Watergate. Under my plan, we will end lobbying as we know it. We will make sure everyone who is paid to influence government is required to register as a lobbyist, and we’ll impose strict disclosure requirements so that lobbyists have to publicly report which agency rules they are seeking to influence and what information they provide to those agencies. We’ll also shut the revolving door between government and K Street to prevent another Trump administration where ex-lobbyists lead the Department of Defense, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Labor, the Department of Interior, and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

My plan also calls for something unique – a new tax on excessive lobbying that applies to every corporation and trade organization that spends over $500,000 per year lobbying our government. This tax will reduce the incentive for excessive lobbying, and raise money that we can use to fight back against this kind of onslaught when it occurs.

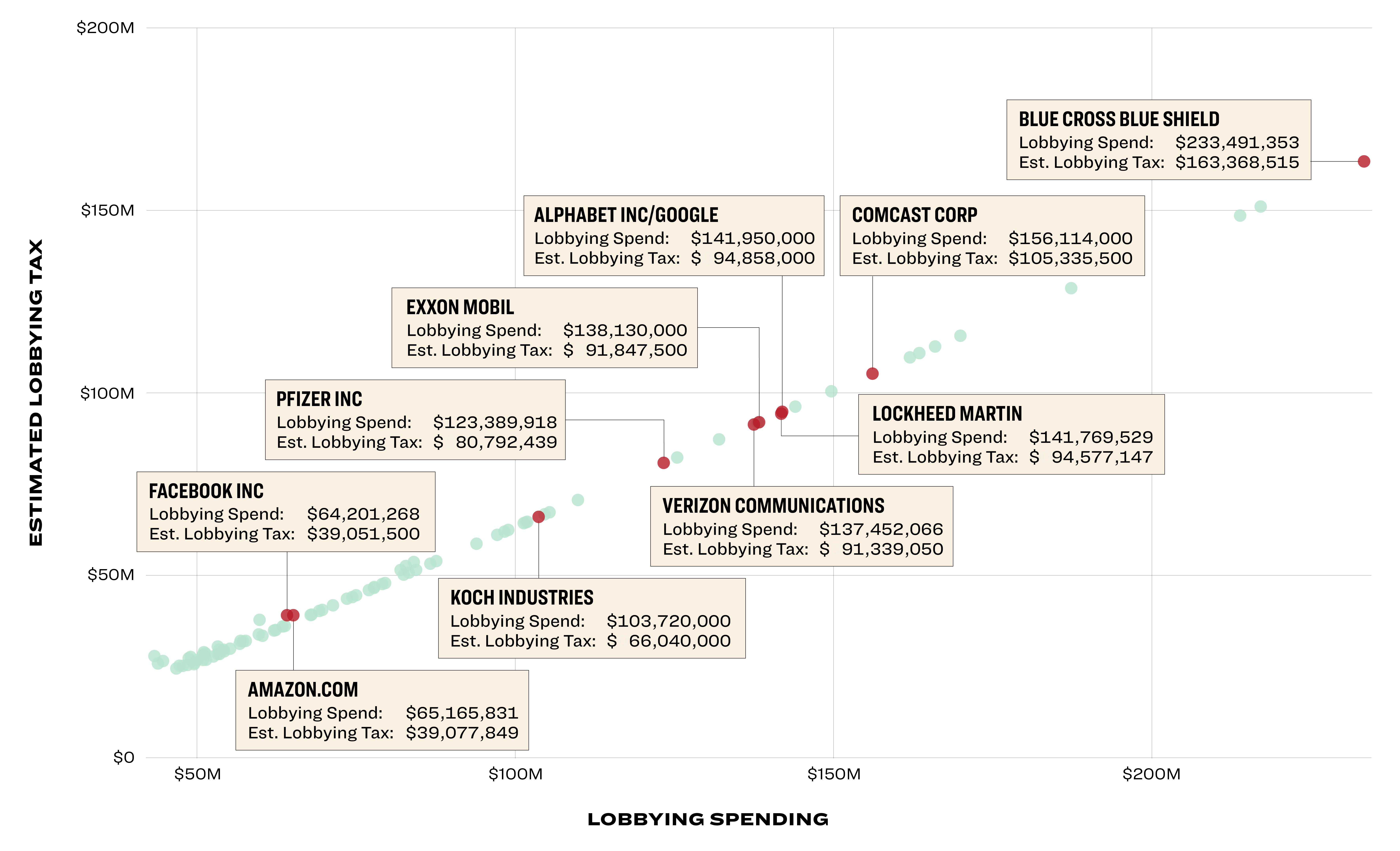

LOBBYING SPENDING AND TAXES (2009-2018)

This chart excludes two outliers–the Chamber of Commerce and National Association of Realtors–whose lobbying expenditures and estimated tax burdens were too large to fit on this chart.

Data provided by Center for Responsive Politics.

Each entity is labeled using the name reported most recently on OpenSecrets.org. View in full screen.Under my lobbying tax proposal, companies that spend between $500,000 and $1 million per year on lobbying, calculated on a quarterly basis, will pay a 35% tax on those expenditures. For every dollar above $1 million spent on lobbying, the rate will increase to 60% – and for every dollar above $5 million, it will increase to 75%.

Based on our analysis of lobbying data provided by the Center for Responsive Politics, if this tax had been in effect over the last 10 years, over 1,600 corporations and trade groups would have had to pay up – leading to an estimated $10 billion in total revenue. And 51 of them – including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Koch Industries, Pfizer, Boeing, Microsoft, Walmart, and Exxon – would have been subject to the 75% rate for lobbying spending above $5 million in every one of those years.

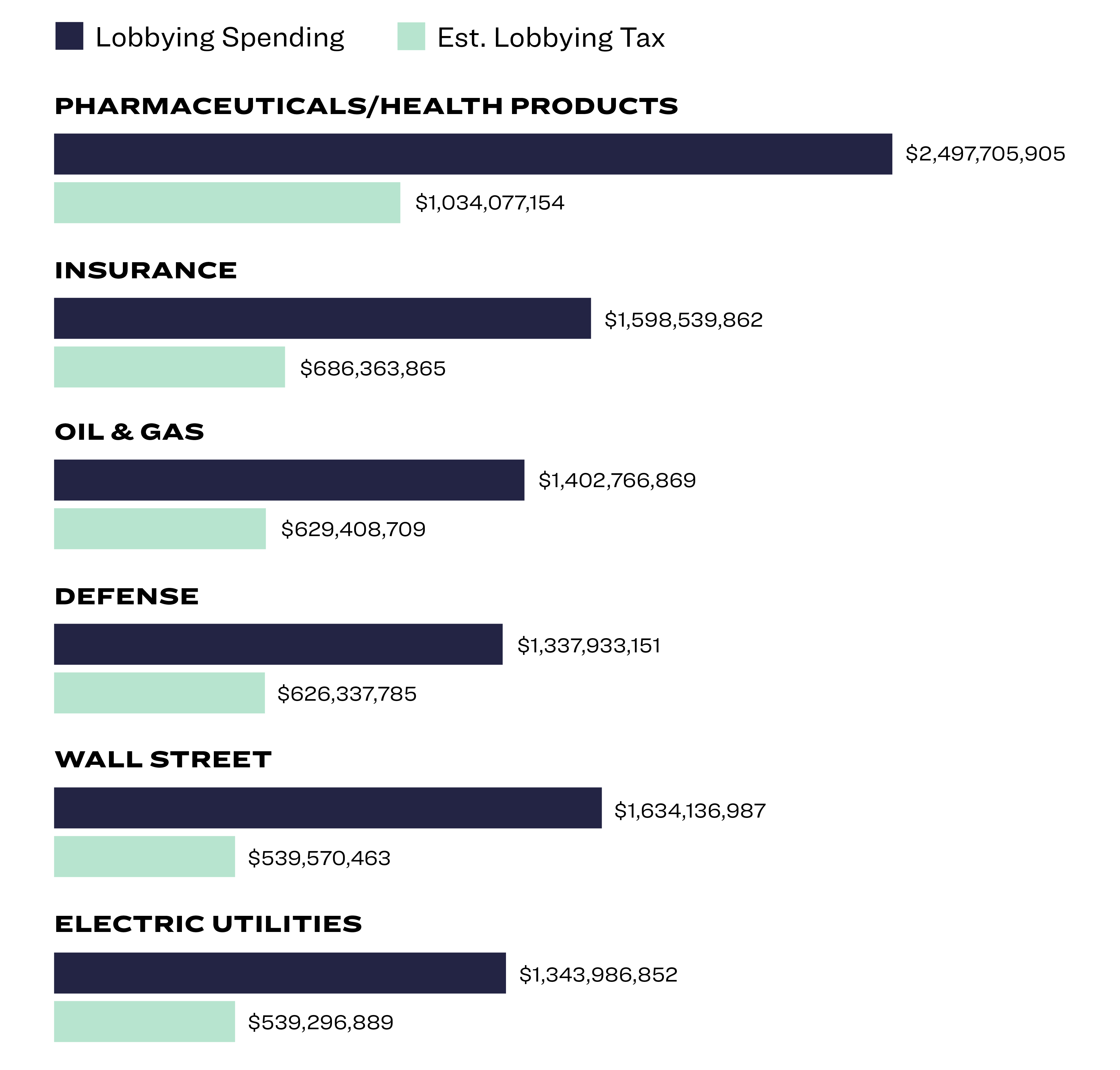

Nobody will be surprised that the top five industries that would have paid the highest lobbying taxes are the same industries that have spent the last decade fighting tooth and nail against popular policies: Big Pharma, health insurance companies, oil and gas companies, Wall Street firms, and electric utilities.

LOBBYING SPENDING AND TAXES BY INDUSTRY (2009-2018)

Data provided by Center for Responsive Politics. View in full screen.

Among individual companies, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce would have owed the most of any company or trade group in lobbying taxes: an estimated $770 million on $1 billion in lobbying spending – over $400 million more than the next-highest-paying organization, the National Association of Realtors, which would have paid $307 million on $425 million in lobbying spending. Blue Cross Blue Shield, PhRMA, and the American Hospital Association would have all paid between $149 and $163 million in taxes on between $213 and $233 million in lobbying spending. And General Electric, Boeing, AT&T, Business Roundtable, and Comcast round out the top ten, paying between $105 million and $129 million in taxes.

Every dollar raised by the lobbying tax will be placed into a new Lobbying Defense Trust Fund dedicated to directing a surge of resources to Congress and federal agencies to fight back against the effort to bury public interest actions by the government.

Corporate lobbyists are experts at killing widely popular policies behind closed doors.

Take just one example from the Obama administration. In October 2010, the Department of Labor (DOL) proposed a “fiduciary rule” to protect employee retirement accounts from brokers who charge exorbitant fees and put their own commissions above earning returns for their clients. The idea was simple: if you’re looking after someone’s money, you should look out for their best interests.

It’s an obvious rule – but it would cut into financial industry profits. So the industry dispatched an army of lobbyists to fight against the rule, including by burying the agency in public comments. In the first four months, the DOL received hundreds of comments on the proposed rule, including comments from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, BlackRock, and other powerful financial interests. After a public hearing with testimony from groups like Fidelity and J.P Morgan, the agency received over 100 more comments - including dozens from members of Congress, many of which were heavily slanted toward industry talking points. Because the law requires agencies to respond to each concern laid out in the public comments, when corporate interests flood agencies with comments, the process often becomes so time-consuming and resource-intensive that it can kill or delay final rules altogether – and that’s exactly what happened. On September 19, 2011, the DOL withdrew the proposed rule, but said that it planned to try again in the future.

Undeterred, Wall Street pushed forward their lobbying campaign to ensure that the Department of Labor wouldn’t try again to re-issue the fiduciary rule. In June 2013, Robert Lewis, a lobbyist for an investment industry trade group, personally drafted a letter opposing this common-sense reform – and got 32 members of Congress to sign it. The letter ominously urged the Department to "learn from its earlier experience" when the financial industry had killed the first proposal. Soon, members of Congress from both parties were joining in, telling the Obama administration to delay re-issuing the rule.

To its great credit, the Obama Department of Labor didn’t give up. On February 23, 2015, the agency finally re-proposed the rule. Wall Street ramped up their lobbying once more to try to kill it a second time. This time, with firm resolve and committed allies, DOL and those of us fighting alongside them beat back thousands of comments, and retirees won – but it took so long that Donald Trump became President before the rule fully went into effect.

Trump came through for Wall Street: the new Administration delayed implementing the rule, and after financial firms spent another $3 million on lobbying at least in part on the rule, the Department of Justice refused to defend it in court. Today, the Department of Labor is led by Eugene Scalia, the very corporate lawyer and ex-lobbyist who brought the lawsuit to kill off the proposal.

Lobbyists have followed this same playbook to block, narrow, or delay countless other common-sense industry regulations. Swarm regulators and Congress, bury everyone in an avalanche of money, and strangle government action in the public interest before it even gets off the ground.

That’s why I’m using the revenue from my tax on excessive lobbying to establish a new Lobbying Defense Trust Fund, which will help our government fight back against the influence of lobbyists.

First, we’ll use the Lobbying Defense Trust Fund to strengthen congressional support agencies. In my plan to strengthen congressional independence from lobbyists, I explained how lobbying tax revenue would help to reinstate the Office of Technology Assessment and increase the budget for other congressional support agencies, like the Congressional Budget Office.

Second, we’ll give more money to federal agencies that are facing significant lobbying activity. Every time a company above the $500,000 threshold spends money lobbying against a rule from a federal agency, the taxes on that spending will go directly to the agency to help it fight back. In 2010, DOL could have used that money to hire more staffers to complete the rule more quickly and intake the flood of industry comments opposing it.

Third, revenue from the lobbying tax will help to establish a new Office of the Public Advocate. This office will help the American people engage with federal agencies and fight for the public interest in the rule-making process. If this office had existed in 2010, the Public Advocate would have made sure that DOL heard from workers and retirees – even while both parties in Congress were spouting industry talking points.

My new lobbying tax will make hiring armies of lobbyists significantly more expensive for the largest corporate influencers like Blue Cross Blue Shield, Boeing, and Comcast. Sure, this may mean that some corporations and industry groups will choose to reduce their lobbying expenditures, raising less tax revenue down the road – but in that case, all the better.

And if instead corporations continue to engage in excessive lobbying, my lobbying tax will raise even more revenue for Congress, agencies, and federal watchdogs to fight back.

It’s just one more example of the kind of big, structural change we need to put power back in the hands of the people – and break the grip that lobbyists have on our government for good.